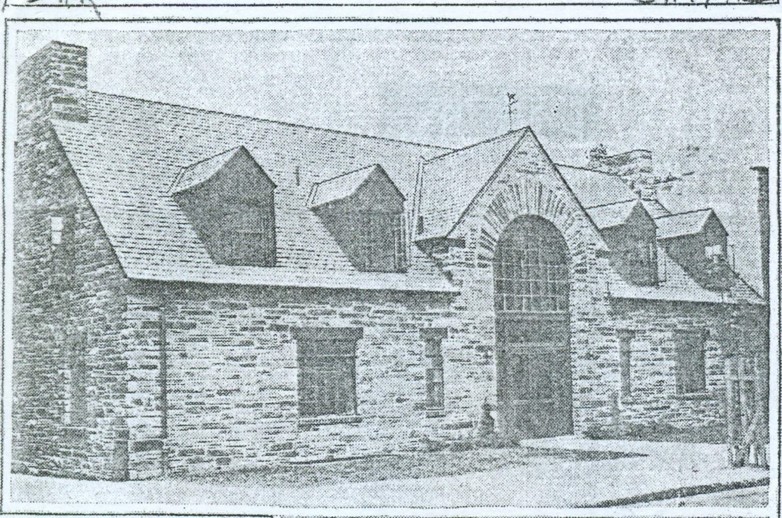

The former Washington Animal Rescue League Shelter and Hospital is located at 71 O Street, NW, and is the pivotal structure representing the development of the animal welfare and humane movement in Washington. This women-founded organization constructed the first purpose-built animal shelter in the history of Washington. WARL’s animal hospital and shelter is the oldest surviving representative of a movement strong in early 20th century America and in Washington, DC to treat animals compassionately. The building is significant for history and architecture.

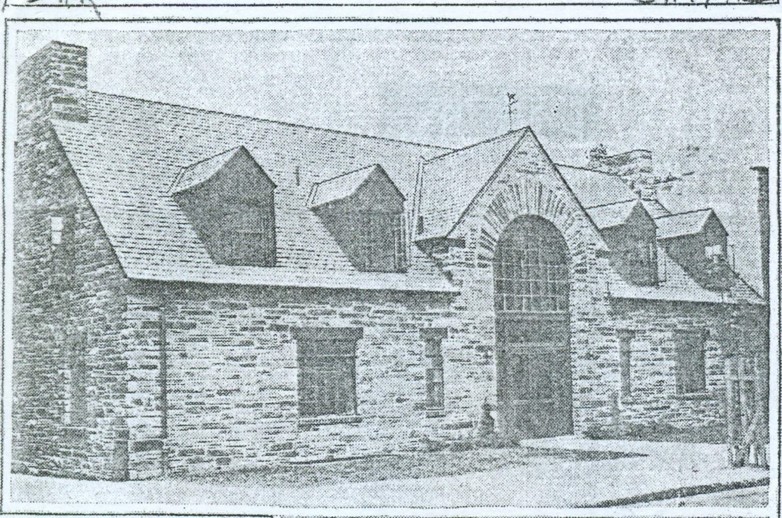

The building was constructed in 1932 and designed by architect and civil engineer Ralph W. Berry in the 20th-century revival style. The builder was Bahen & Wright.

Today the building continues to serve a civic function as the offices of non-profit So Others Might Eat, known as SOME.

Origins of the Humane Movement in Washington

Laws banning cruelty to animals in the District of Columbia date from 1819. In 1870, the District’s first specific organization dedicated to dealing with this problem was created, the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA). The SPCA was renamed the Washington Humane Society (WHS) in 1885, focused solely on the treatment of animals both on the street and in other circumstances, but did not shelter animals. This task was left to the District pound.

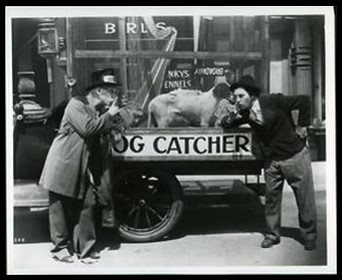

From its establishment in 1872, the pound took stray and unlicensed farm animals and dogs from the city streets and held them for three days, making them available for redemption by their owners or purchase by others, before euthanizing them. Aside from distressed owners who had to go to the pound and pay a small charge to get back their livestock or pets, records suggest that there were no major complaints during the 19th and early 20th centuries about the treatment of animals at the pound.

Nonetheless, activists increasingly felt the need for an effort to house and place abandoned animals that emphasized the welfare of the animals rather than their control, like the pound. WHS operated a shelter on 19th Street and Columbia Road, NW from 1897-1899 that took in cats and dogs. Unlike the pound, it did not take animals directly from the street but only those brought in by the public. Like the pound, those not reclaimed or purchased were put down. The endeavor soon ran into the same problems that would doom its immediate successors: the constant need of funds for even its barebones operation and the demand for its land from a growing city, in this case, planned widening of 19th Street.

The first decade and a half of the new century saw attempts to establish animal shelters by a variety of well-meaning but short-lived organizations, including a second WHS shelter, Mrs. Beckley’s Cat Shelter, the Friendly Hand Society, and the Society for Homeless Dogs. All of these groups took in animals and all succumbed to similar problems. An additional issue was neighborhood complaints about the noise of the animals; most were sited outside the District for this reason.

Origins of the Washington Animal Rescue League (WARL)

The shelter movement in Washington lay dormant for a few years after the demise of these early efforts. The genesis of its more successful modern stage was a 1914 effort by two women to take the owners of mistreated horses to court, after which they were moved to concern themselves with the plight of cats, dogs, and horses across Washington.

One of these women was Matilde Goelet Gerry, who became the leading force in the renewed effort. She and her friends invited Anna Harris Smith, founder of Boston’s Animal Rescue League and crusader for the movement, to meet them informally and outline the possibilities. Smith served as the keynote speaker at the public organizing meeting of the new Washington Animal Rescue League held at the Woodward & Lothrop Department Store auditorium on March 31st, 1914. A second meeting the following month formally enrolled members and elected officers, and the organization adopted by-laws and incorporated in DC on April 14th of the same year. The goal of the initial resolutions was “that an animal hospital and shelter be established in Washington.”

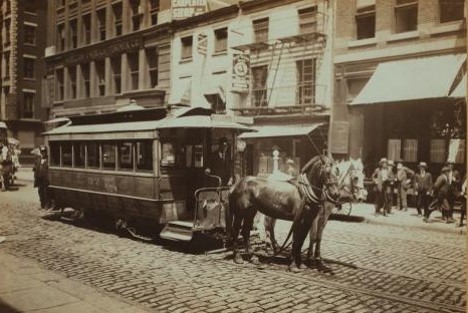

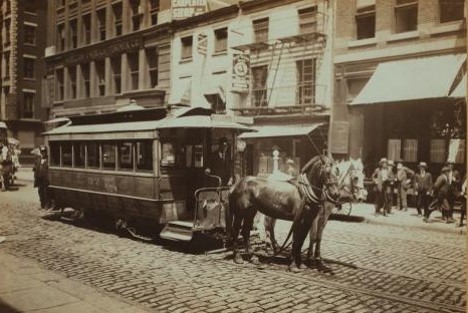

Three assumptions initially guided WARL: a primary concern with horses. Gerry was a noted horsewoman. The earliest League record gives its purpose as “the proper disposition of decrepit and injured horses and other animals.” However, dogs and cats always provided the bulk of the League’s work; horses were already disappearing from Washington streets. The shift spared WARL from the dead-end that made WHS nearly irrelevant.

The second assumption was that the League would be largely an organization of women. The organizers specified a “mixed board of men and women to assure business-like management,” and were “especially anxious to have representative men as vice-presidents . . . to assure standing in the community.” Nonetheless, the by-laws always referred to the president as She. Men were generally represented among WARL officers, but the majority was always female, and there were years in which every officer and the entire Board of Directors were women.

Finally, the League was an effort of affluent and socially well-connected Washingtonians. This is clear from the lists of event organizers and attendees, of officers and members, of the prestigious venues of meetings and fundraisers. There are no mentions of middle and working-class people, nor a focus on any type of diversity, except for gender.

The primary object of the new League was the rescue of friendless horses, dogs, and cats from city streets, or – in the case of horses – from abusive owners, usually by purchase. The animals’ injuries were treated and then returned to their original owners, if suitable, or found a new home. WARL was clear from the beginning that unwanted or severely injured animals would be humanely put down. Initially, this was done with chloroform.

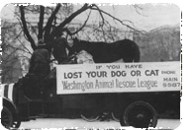

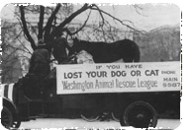

From its earliest years, the WARL shelter also operated a contractor medical clinic – initially open one hour every morning and geared toward horses, free for minor services and at “moderate charge . . . for medicines and for surgical operations.” A boarding service was also envisioned, as had been done by its predecessors. More ambitious plans considered at the March meeting included the purchase of “a horse ambulance and a dog ambulance,” an automobile, and “a special bicycle” (“for carrying injured cats”) and a rest home “for run-down horses.”

WARL’s Shelters and Operations

The League first opened a shelter in a few rooms over a stable at 20 Decatur Street NE on May 10th, 1914 with Mary E. Coursey as manager. Coursey had run a Boston shelter for fifteen years. She was joined by two assistants. In its first full month of operation, the shelter took in 365 cats, 19 dogs, and 2 horses. Sadly the dogs and cats were euthanized. Healthy horses were sent to new owners, the seriously ailing were euthanized.

WARL’s founders and at least some members of the public seemed to think the organization superior to the Pound, with its focus on control rather than compassion. Prominent supporters bolstered this confidence: Ms. West of the Washington Cat Club and Madame Bey, wife of the Turkish ambassador, were members, as was Edith Wilson, the first in a line of First Lady supporters. Prominent actor George Arliss championed participation by men but feared that “people wouldn’t listen to an actor off the stage.”

The number of animals brought to WARL quickly required a move to a larger facility on Ohio Avenue; in August 1915 alone the shelter took in 743 dogs and cats. The League increasingly adopted out animals, especially cats.

Horses were typically purchased from owners – in its first full year of operation 69 were bought. WARL’s early efforts included the provision of “a kind of carpet slipper” allowing horses to get traction on snow-covered streets, and encouraging MPD officers to report abused animals to the shelter. In general, the operation of the shelter remained WARL’s focus.

A visitor of 1915 wrote: “The system is remarkable . . . I was so impressed by the place that I feel every man, woman, and child should visit.” Nonetheless, a headline of two years later tells the usual story: “Residents of Ohio Avenue Opposed to Rescued Animals in Neighborhood.” Among other complaints in the residents’ petition to local government was that dead animals were not picked up promptly, resulting in a terrible smell. WARL’s continued growth and neighborhood opposition soon brought about a move to Maryland Avenue, where it remained for many years.

71 O Street NW Hospital and Shelter

Finally in 1932 WARL made the momentous move to its first purpose-built shelter, the building at 71 O Street NW. The impetus for this project was an increasing need for space and facility, as well as the National Capital Park and Planning Commission plan to develop the District’s immediate southwest area as a government enclave. Sale of the Maryland Avenue property to the District government paid for most of the new property.

The community into which WARL moved – near Truxton Circle about a mile north of the Capitol – was a long-established area by 1932. Warehouses and workshops, especially garages and auto repair shops, increasingly crowded against the working-class residents. Neighboring Swampoodle, had already seen working-class residents displaced by light industry.

The League’s Real Estate and Building Committee first considered a site at South Capitol and D Streets SW, which was near its current shelter and the pound. However, a few congressmen objected to the hospital so close to their offices. The O Street site was the next choice. O Street protested too: neighbors hired a downtown law firm to protest the shelter as a non-conforming use in violation of zoning regulations. The Commissioners disagreed and permitted the animal hospital, but limited it to 40 animals.

Architect Ralph W. Berry

The new shelter was about one block west of the League’s first, rented space on Decatur Street. Architect Ralph W. Berry received the contract to plan (in separate jobs) the street-facing shelter/office and, on the rear alley, a garage. Berry designed nearly 100 houses in the District and others in Montgomery County, Maryland, between 1923 and 1937, almost all brick or stone structures in the wealthy upper-northwest area. This was a rare non-residential building for him.

Berry and League officials visited shelters in New York, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New Orleans. The architect submitted his proposal to the federal Commission of Fine Arts for an advisory-only opinion, featuring an English façade of Potomac River gneiss over a brick structure. The Commission found the design “good” but felt that a stone structure was “more appropriate for a suburban type of building” and recommended its then-standard “Georgian brick building.” Berry ignored this advice. Bahen & Wright, a general contractor active in the eastern half of the city 1926-1940, was selected as the builder.

The project faced a few challenges, such as delay in the removal of the old warehouse, readjustment of plans, and permitting issues. When excavation began, water and bad soil necessitated a different foundation. The last added $6,260 in costs, bringing the project cost to about $26,000.

Opening and Use of 71 O Street, NW

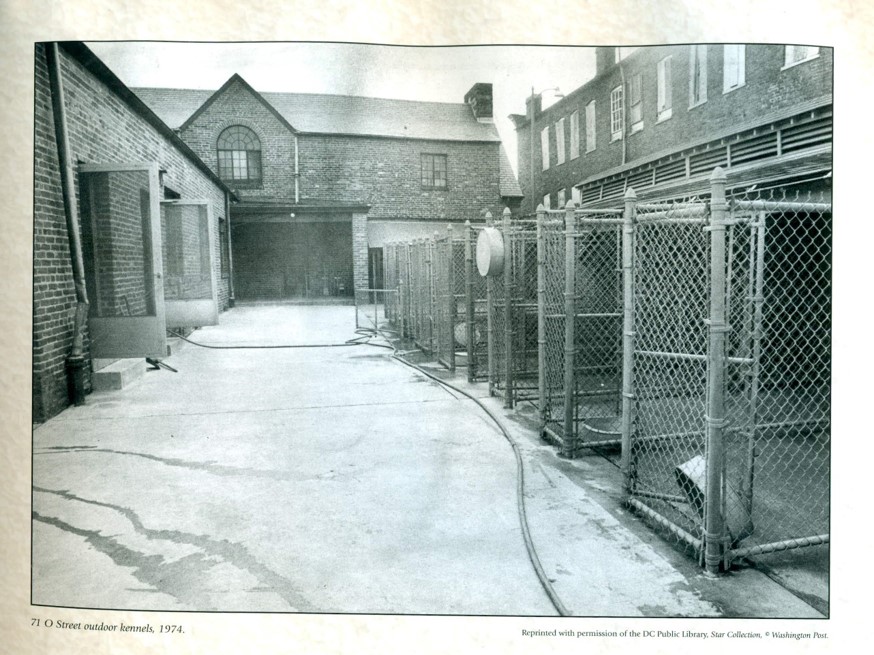

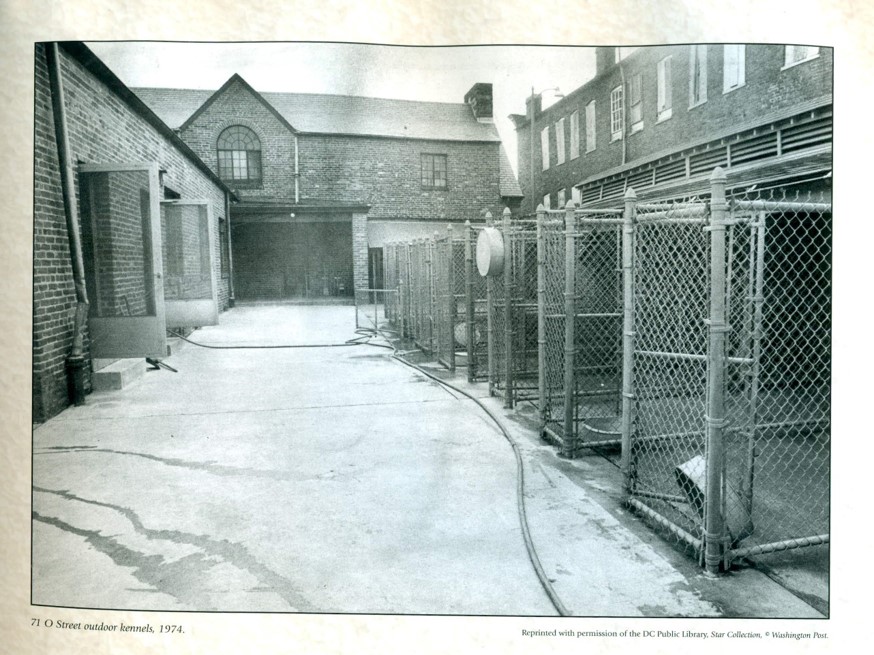

The shelter opened with an invitation-only ceremony on June 23rd, 1932. Visitors and reporters, were impressed, calling it, “The most modern and well-equipped facilities for the care and shelter of stray and sick beasts,” “thoroughly insulated and fireproofed,” and “safe, sanitary and comfortable accommodations.” With its 50 cages for dogs and a dozen cat cages, separate runs for each, veterinary clinic, two “comfortable” stalls for horses (in the garage), and an upstairs caretaker’s apartment, “the new building compares favorably with the best anywhere” – “a credit to the City and to the Directors.”

Cages bore the names of donors and a plaque in the main hall commemorated the 1917 donation of the earlier building by Martha Codman and Chester Snow, which later paid for the new one. League members made donations of shrubbery, the paved walk & office furniture.

Upon opening, the building already held 40 dogs and 12 cats. In its new quarters, the League increased its clinic service to three veterinarians. Through an agreement with the District government, city-owned horses that were retired in favor of trucks went to WARL, which placed healthy ones in nearby farms. At the same time, routine ambulance runs to take pets from homes dropped back from daily to four days a week, though the truck was available 24 hours a day for injured animals. Educational outreach grew in scope. The League’s work at O Street continued smoothly, with a larger staff, more professional operations and continued harmonious governance.

By the mid-1960s the facility clearly required updating. The District government was not supportive, announcing that it planned to take the property for a school playground. Although this threat receded, WARL began a five-year search for larger quarters, moving 71 Oglethorpe Street NW, at the very edge of the District, in 1977, where it still operates today.

Significance

The Washington Animal Rescue League animal hospital and shelter is the pivotal structure representing the development of the animal welfare and humane movement in Washington. Earlier animal shelters opened by other organizations prior to 1910 were essentially shacks with wire-fenced pens, and all soon closed. The WARL gave a temporary home for any abandoned animal – principally dogs, cats, horses – brought to its premises; its work continues today. In 1932, having outgrown its last facility and facing eviction from the city government for road construction, WARL made the momentous decision to construct the first purpose-built animal shelter in the history of Washington, the present building on O Street. The new structure was praised as the acme of modern efficiency and comfort for the animal-tenants. It served as a model for WARL’s current building on Oglethorpe Street.

The women founded WARL animal hospital and shelter is the oldest surviving representative of a movement strong in early 20th century America and in Washington, DC to treat all animals with love and care, complementing the parallel work of the District pound. As a reminder of its central role in this civic and humanitarian effort by the citizens of Washington the building is significant for its history and its architecture.

The DC Historic Preservation Review Board (HPRB) designated the building a DC Landmark in December 2018 for meeting criteria for history and for architecture. Click here to read the HPRB decision.

Click here to learn more about the Washington Animal Rescue League now known as the Humane Rescue Alliance.

Click here to learn more about So Others Might Eat.

The former Washington Animal Rescue League Shelter and Hospital is located at 71 O Street, NW, and is the pivotal structure representing the development of the animal welfare and humane movement in Washington. This women-founded organization constructed the first purpose-built animal shelter in the history of Washington. WARL’s animal hospital and shelter is the oldest surviving representative of a movement strong in early 20th century America and in Washington, DC to treat animals compassionately. The building is significant for history and architecture.

The building was constructed in 1932 and designed by architect and civil engineer Ralph W. Berry in the 20th century revival style. The builder was Bahen & Wright.

Today the building continues to serve a civic function as the offices of non-profit So Others Might Eat, known as SOME.

Origins of the Humane Movement in Washington

Laws banning cruelty to animals in the District of Columbia date from 1819. In 1870, the District’s first specific organization dedicated to dealing with this problem was created, the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA). The SPCA, renamed the Washington Humane Society (WHS) in 1885, focused solely on the treatment of animals both on the street and in other circumstances, but did not shelter animals. This task was left to the District pound..

From its establishment in 1872, the pound took stray and unlicensed farm animals and dogs from the city streets and held them for three days, making them available for redemption by their owners or purchase by others, before euthanizing them. Aside from distressed owners who had to go to the pound and pay a small charge to get back their livestock or pets, records suggest that there were no major complaints during the 19th and early 20th centuries about the treatment of animals at the pound.

Nonetheless, activists increasingly felt the need for an effort to house and place abandoned animals that emphasized the welfare of the animals rather than their control, like the pound. WHS operated a shelter on 19th Street and Columbia Road, NW from 1897-1899 that took in cats and dogs. Unlike the pound, it did not take animals directly from the street but only those brought in by the public. Like the pound, those not reclaimed or purchased were put down. The endeavor soon ran into the same problems that would doom its immediate successors: the constant need of funds for even its barebones operation and the demand for its land from a growing city, in this case, planned widening of 19th Street.

The first decade and a half of the new century saw attempts to establish animal shelters by a variety of well-meaning but short-lived organizations, including a second WHS shelter, Mrs. Beckley’s Cat Shelter, the Friendly Hand Society, and the Society for Homeless Dogs. All of these groups took in animals and all succumbed to similar problems. An additional issue was neighborhood complaint about the noise of the animals; most were sited outside the District for this reason.

Origins of the Washington Animal Rescue League (WARL)

The shelter movement in Washington lay dormant for a few years after the demise of these early efforts. The genesis of its more successful modern stage was a 1914 effort by two women to take the owners of mistreated horses to court, after which they were moved to concern themselves with the plight of cats, dogs, and horses across Washington.

One of these women was Matilde Goelet Gerry, who became the leading force in the renewed effort. She and her friends invited Anna Harris Smith, founder of Boston’s Animal Rescue League and crusader for the movement, to meet them informally and outline the possibilities. Smith served as the keynote speaker at the public organizing meeting of the new Washington Animal Rescue League held at the Woodward & Lothrop Department Store auditorium on March 31st, 1914. A second meeting the following month formally enrolled members and elected officers, and the organization adopted by-laws and incorporated in DC on April 14th of the same year. The goal of the initial resolutions was “that an animal hospital and shelter be established in Washington.”

Painted by John Singer Sargent, 1907

Three assumptions initially guided WARL: a primary concern with horses. Gerry was a noted horsewoman. The earliest League record gives its purpose as “the proper disposition of decrepit and injured horses and other animals.” However, dogs and cats always provided the bulk of the League’s work; horses were already disappearing from Washington streets. The shift spared WARL from the dead-end that made WHS nearly irrelevant.

The second assumption was that the League would be largely an organization of women. The organizers specified a “mixed board of men and women to assure business-like management,” and were “especially anxious to have representative men as vice-presidents . . . to assure standing in the community.” Nonetheless, the by-laws always referred to the president as She. Men were generally represented among WARL officers, but the majority was always female, and there were years in which every officer and the entire Board of Directors were women.

Finally, the League was an effort of affluent and socially well-connected Washingtonians. This is clear from the lists of event organizers and attendees, of officers and members, of the prestigious venues of meetings and fundraisers. There are no mentions of middle and working class people, nor a focus on any type of diversity, except for gender.

The primary object of the new League was the rescue of friendless horses, dogs and cats from city streets, or – in the case of horses – from abusive owners, usually by purchase. The animals’ injuries were treated and then returned to their original owners, if suitable, or found a new home. WARL was clear from the beginning that unwanted or severely injured animals would be humanely put down. Initially this was done with chloroform.

From its earliest time the WARL shelter also operated a contractor medical clinic – initially open one hour every morning and geared toward horses, free for minor services and at “moderate charge . . . for medicines and for surgical operations.” A boarding service was also envisioned, as had been done by its predecessors. More ambitious plans considered at the March meeting included purchase of “a horse ambulance and a dog ambulance,” an automobile, and “a special bicycle” (“for carrying injured cats”) and a rest home “for run-down horses.”

WARL’s Shelters and Operations

The League first opened a shelter in a few rooms over a stable at 20 Decatur Street NE on May 10th, 1914 with Mary E. Coursey as manager. Coursey had run a Boston shelter for fifteen years. She was joined by two assistants. In its first full month of operation the shelter took in 365 cats, 19 dogs, and 2 horses. Sadly the dogs and cats were euthanized. Healthy horses were sent to new owners, the seriously ailing were euthanized.

WARL’s founders and at least some members of the public seemed to think the organization superior to the Pound, with its focus on control rather than compassion. Prominent supporters bolstered this confidence: Ms. West of the Washington Cat Club and Madame Bey, wife of the Turkish ambassador, were members, as was Edith Wilson, the first in a line of First Lady supporters. Prominent actor George Arliss championed participation by men but feared that “people wouldn’t listen to an actor off the stage.”

The number of animals brought to WARL quickly required a move to a larger facility on Ohio Avenue; in August 1915 alone the shelter took in 743 dogs and cats. The League increasingly adopted out animals, especially cats.

Horses were typically purchased from owners – in its first full year of operation 69 were bought. WARL’s early efforts included the provision of “a kind of carpet slipper” allowing horses to get traction on snow-covered streets, and encouraging MPD officers to report abused animals to the shelter. In general, operation of the shelter remained WARL’s focus.

A visitor of 1915 wrote: “The system in remarkable . . . I was so impressed by the place that I feel every man, woman and child should visit.” Nonetheless, a headline of two years later tells the usual story: “Residents of Ohio Avenue Opposed to Rescued Animals in Neighborhood.” Among other complaints in the residents’ petition to local government was that dead animals were not picked up promptly, resulting in a terrible smell. WARL’s continued growth and neighborhood opposition soon brought about a move to Maryland Avenue, where it remained for many years.

71 O Street NW Hospital and Shelter

Finally in 1932 WARL made the momentous move to its first purpose-built shelter, the building at 71 O Street NW. The impetus for this project was an increasing need for space and facility, as well as the National Capital Park and Planning Commission plan to develop the District’s immediate southwest area as a government enclave. Sale of the Maryland Avenue property to the District government paid for most of the new property.

The community into which WARL moved – near Truxton Circle about a mile north of the Capitol – was a long-established area by 1932. Warehouses and workshops, especially garages and auto repair shops, increasingly crowded against the working class residents. Neighboring Swampoodle, had already seen working class residents displaced by light industry.

The League’s Real Estate and Building Committee first considered a site at South Capitol and D Streets SW, which was near its current shelter and the pound. However, a few congressmen objected to the hospital so close to their offices. The O Street site was the next choice. O Street protested too: neighbors hired a downtown law firm to protest the shelter as a non-conforming use in violation of zoning regulations. The Commissioners disagreed and permitted the animal hospital, but limited it to 40 animals.

Architect Ralph W. Berry

The new shelter was about one block west of the League’s first, rented space on Decatur Street. Architect Ralph W. Berry received the contract to plan (in separate jobs) the street-facing shelter/office and, on the rear alley, a garage. Berry designed nearly 100 houses in the District and others in Montgomery County, Maryland, between 1923 and 1937, almost all brick or stone structures in the wealthy upper-northwest area. This was a rare non-residential building for him.

Berry and League officials visited shelters in New York, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New Orleans. The architect submitted his proposal to the federal Commission of Fine Arts for an advisory-only opinion, featuring an English façade of Potomac River gneiss over a brick structure. The Commission found the design “good” but felt that a stone structure was “more appropriate for a suburban type of building” and recommended its then-standard “Georgian brick building.” Berry ignored this advice. Bahen & Wright, a general contractor active in the eastern half of city 1926-1940, was selected as the builder.

The project faced a few challenges, such as delay in removal of the old warehouse, readjustment of plans, and permitting issues. When excavation began, water and bad soil necessitated a different foundation. The last added $6,260 in costs, bringing the project cost to about $26,000.

Opening and Use of 71 O Street, NW

The shelter opened with an invitation-only ceremony on June 23rd, 1932. Visitors and reporters, were impressed, calling it, “The most modern and well-equipped facilities for the care and shelter of stray and sick beasts,” “thoroughly insulated and fireproofed,” and “safe, sanitary and comfortable accommodations.” With its 50 cages for dogs and a dozen cat cages, separate runs for each, veterinary clinic, two “comfortable” stalls for horses (in the garage), and an upstairs caretaker’s apartment, “the new building compares favorably with the best anywhere” – “a credit to the City and to the Directors.”

Cages bore the names of donors and a plaque in the main hall commemorated the 1917 donation of the earlier building by Martha Codman and Chester Snow, which later paid for the new one. League members made donations of shrubbery, the paved walk & office furniture.

At its inauguration the building already held 40 dogs and 12 cats. In its new quarters the League increased its clinic service to three veterinarians. Through an agreement with the District government, city-owned horses retired in favor of trucks went to WARL, which placed healthy ones in nearby farms. At the same time, routine ambulance runs to take pets from homes dropped back from daily to four days a week, though the truck was available 24 hours a day for injured animals. Educational outreach grew in scope. The League’s work at O Street continued smoothly, with a larger staff, more professional operations and continued harmonious governance.

By the mid-1960s the facility clearly required updating. The District government was not supportive, announcing that it planned to take the property for a school playground. Although this threat receded, WARL began a five-year search for larger quarters, moving 71 Oglethorpe Street NW, at the very edge of the District, in 1977, where it still operates today.

Significance

The Washington Animal Rescue League animal hospital and shelter is the pivotal structure representing the development of the animal welfare and humane movement in Washington. Earlier animal shelters opened by other organizations prior to 1910 were essentially shacks with wire-fenced pens, and all soon closed. The WARL gave a temporary home for any abandoned animal – principally dogs, cats, horses – brought to its premises; its work continues today. In 1932, having outgrown its last facility and facing eviction from the city government for road construction, WARL made the momentous decision to construct the first purpose-built animal shelter in the history of Washington, the present building on O Street. The new structure was praised as the acme of modern efficiency and comfort for the animal-tenants. It served as a model for WARL’s current building on Oglethorpe Street.

The women founded WARL animal hospital and shelter is the oldest surviving representative of a movement strong in early 20th century America and in Washington, DC to treat all animals with love and care, complementing the parallel work of the District pound. As a reminder of its central role in this civic and humanitarian effort by the citizens of Washington the building is significant for its history and its architecture.

The DC Historic Preservation Review Board (HPRB) designated the building a DC Landmark in December 2018 for meeting criteria for history and for architecture. Click here to read the HPRB decision.

Click here to learn more about the Washington Animal Rescue League now known as the Humane Rescue Alliance.

Click here to learn more about So Others Might Eat.